(Or: “Well, That’s a Learning Experience” in Disguise) Now, I’m not saying you would make any of these errors. But other people — let’s call them...

read more

Maintenance & Longevity

(Or: How to Keep Your Rattan From Turning Into Regret Over the Next Decade) You’ve done it. The rattan is attached, the glue is dry, the trim is on,...

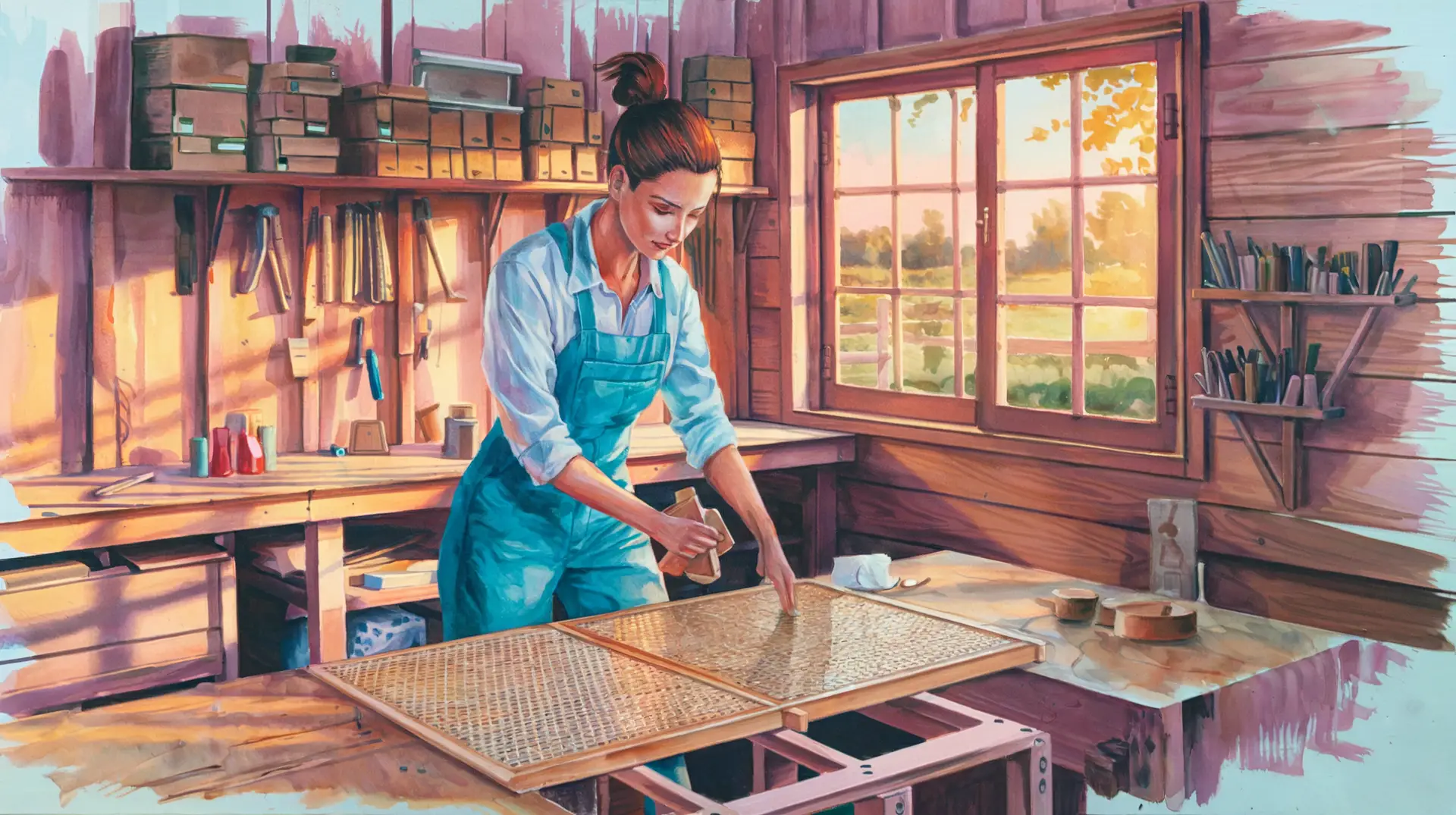

Application Techniques

(Or: How to Attach Rattan to Flat Panels, Curved Surfaces, and Your Loftiest Aspirations) Now that you’ve selected your materials, soaked your...

Choosing Your Rattan and Wood (The Marriage of Wicker and Tree)

Every epic tale begins with a union. Helen of Troy had her face, Arthur had his sword, and you, dear reader, have choices. Before a single staple is...

Preparation Steps

aka..( How to Bathe Your Cane and Convince the Wood It’s Ready for Commitment) Before any rattan meets wood in holy (or slightly sticky) matrimony,...